The Psychology of Adult Learning

Customer conversations

An education professor at the University of Chicago once coined the term “hidden curriculum.”

The phrase suggests that schools teach more than just the material covered in class. They also teach unseen norms. Often, these norms include methods of learning based on an outdated understanding of the brain. As a result, many of us are anchored to routines in learning that don’t serve us as well as they should. We carry these norms with us into adulthood and professional training.

The good news: we can change the way we learn. This change is called neuroplasticity.

Neuroplasticity is the remodeling of neural networks. Neuroplasticity shows us that synaptic connections are constantly forming. This is good news because it means we can also change the way we learn by adopting new methods supported by psychological research. Effective and efficient learning is becoming a competitive advantage in a world where information is limitless and accessible to all.

Here we take a renewed look at learning to explore new ways to connect with new information. We also offer explicit tips to help you leverage the full value of professional training for yourself or your team.

Learning Style Matters Less Than You Think

Most of us have a preferred learning style. Some refer to themselves as “visual learners.” Others believe they are “verbal learners” or “logical learners.” While these preferences are genuine, their importance to learning has long been overstated. Simply put: learning styles don’t matter as much as many of us believe.

This discovery is the work of four researchers published in the academic journal, Psychological Science in the Public Interest. They examined the “meshing hypothesis,” which is the idea that instruction is most effective when the lesson is presented in a format that matches the learner’s preferred style. After a rigorous review of existing research, they learned that “there is no adequate evidence base to justify incorporating learning styles assessments into general educational practice.”

More interestingly, they learned that something else is more important for effective learning: selecting the mode of instruction based on the subject matter rather than the learner. Here, we look at why the popular “meshing hypothesis” is a problem and three better approaches to learning that can benefit anyone.

How Learning Got Off Track

The practice of categorizing people into “types” dates to the 1940s when the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator test became a popular personality matrix. The widespread adoption of the test gave rise to the assumption that people fit neatly into well-defined groups. The test enjoys “much intuitive appeal,” as researchers in the Consulting Psychology Journal explain, but “may not yet be able to support the claims its promoters make.” Despite a lack of support from researchers, the test remains in use today.

However, what is more problematic is that the popularity of the test encouraged the adoption of “type-based” learning. Since then, many have embraced the notion that learning should match one’s preferred delivery style. Unfortunately, this movement ignores the idea that preference doesn’t dictate proficiency. The researchers also explain that type based learning puts the responsibility on the lesson, not the learner.

Instead, the method of teaching has more to do with the learner’s prior knowledge, not their “learning style.” Despite this truth, the strategy of matching instruction to learning style is widespread. This thinking leads many to limit themselves to only the material that suits their “style.” Too often, we select learning material based on its format. Doing so ignores a range of other useful material that would bolster skill development.

Becoming a more effective learner means abandoning the meshing hypothesis and focusing on three key learning traits.

Three Ways for Anyone to Boost Learning

Perceptual Learning: Perceptual learning is the practice of learning to distinguish the difference between two or more things. For example, perceptual learning is what makes it possible for a musician to tell the difference between two nearly identical notes played. The act of distinguishing nuanced differences helps a learner better understand the material. In doing so, learners become adept at determining what information is important and what is not.Putting perceptual learning into effect means avoiding a surface reading of the simple features of the pertinent material. Instead, it’s critical to delve deeper and articulate the detailed differences between interrelated concepts. This approach doesn’t demand an excessive time commitment from the learner because perceptual learning is also about developing the skill to quickly identify the critical information. It’s important to be selective in choosing what to focus on. Perceptual learning works because it goes deeper than common, traditional approaches like declarative learning or procedural learning. Declarative learning is simply the retention of facts. Procedural learning is the ability to memorize a series of steps in a process, like changing a tire. Perceptual learning is different because it encourages learners to truly understand the material rather than memorize.

Cooperative Learning: Cooperative learning seeks to develop the individual’s skills through group engagement. The effectiveness of cooperative learning is that participants share knowledge and work together to make each other’s understanding of the material complete. Moreover, cooperative learning avoids the competitiveness that often creeps into learning environments. Students become active participants in the learning process rather than relying entirely on the instructor.

Social Interdependence Theory forms the basis of cooperative learning. Social Interdependence Theory suggests that in a group setting, everyone’s accomplishment are influenced by other team members. Cooperative learning aims to achieve “positive interdependence” in which each person recognizes that reaching their goal requires group cooperation. The connection to this theory is important because “social interdependence theory is validated by hundreds of research studies indicating that cooperation, compared to competitive and individualistic efforts, tends to result in greater achievement,” according to research published in Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning.

Making cooperative learning work means fostering:

- Engagement among learners

- Individual accountability

- Trust and communication

- Reflection on group effectiveness

- In-person interaction

Becoming a better learner means forgetting learning types. Studies have not provided conclusive evidence that people can be attributed to a learning style. Instead, learners can be more effective with a focus on other, proven methods.

- Take the time to delve into the details of the material and understand the nuanced differences between the interrelated topics

- Seek opportunities for group learning in which the process of skill development is shared

- Use verbal and visual cues together — doing so might require drafting quick sketches of abstract concepts

The Power of Interleaving for Retention

Most textbooks are wrong. The information within them is correct; however, the way the information is organized is flawed.

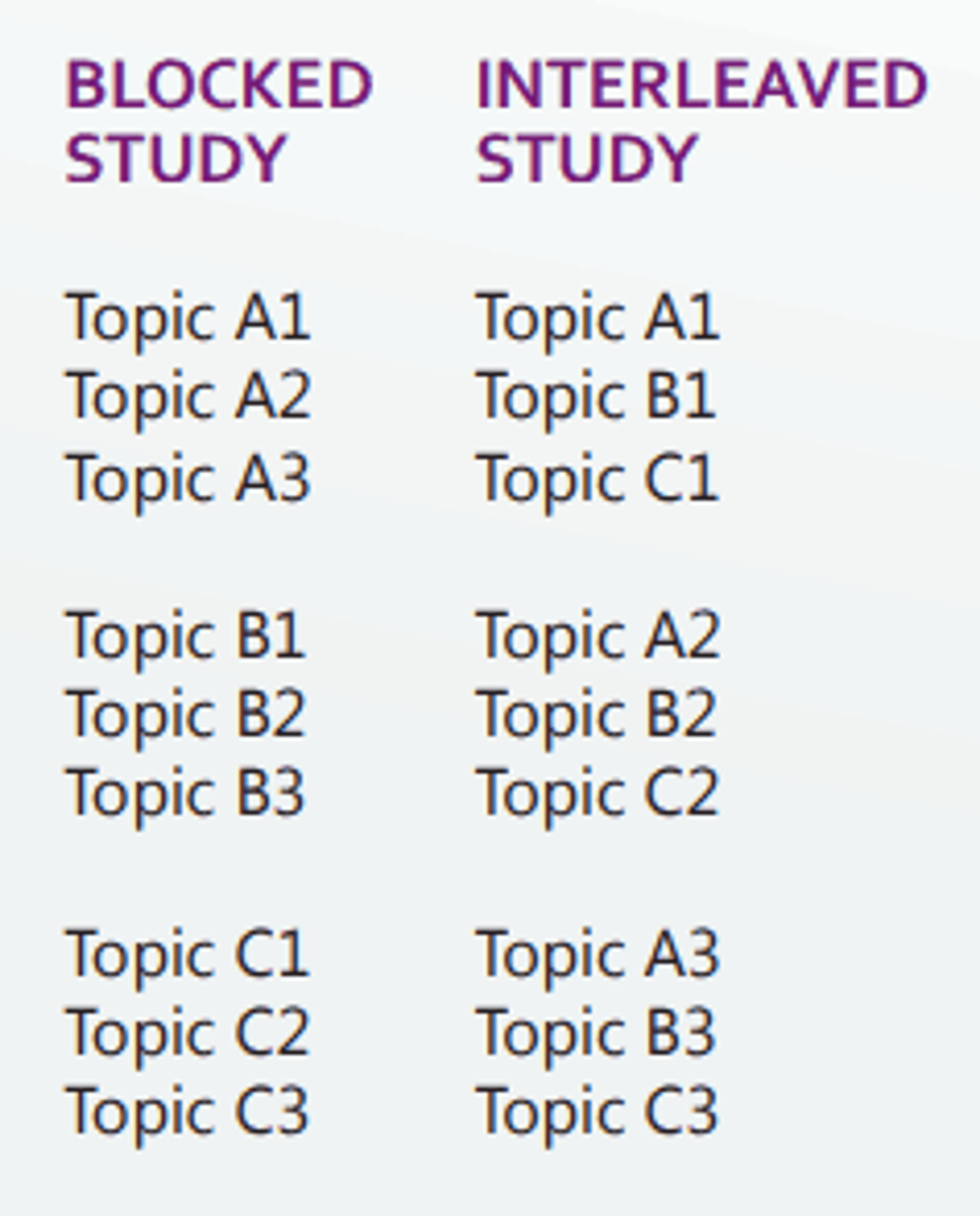

Textbooks present information in a “blocked” format. This style means that information is separated by topic. For example, the first chapter of a chemistry text will discuss atoms. The next section will move on to solution compositions, then chemical reactions. This tiered structure suggests that each topic should be mastered before moving to the next section, a practice called blocked study.

The problem with this approach is that it ignores something called “interleaving study,” which is important because “research in skill acquisition has demonstrated a clear advantage for interleaved study,” according to work published in Frontiers in Psychology.

Interleaved study is the practice of alternating between topics instead of moving through them linearly. An interleaved approach means that the chemistry student would learn about solution compositions while learning about atoms instead of one before the other. Here, we look at why interleaving accelerates learning, how to use it, and the implications for sales professionals seeking to bolster their skillset.

Why Interleaving Works

The researchers wanted to understand why interleaving works. They discovered that the effectiveness behind the strategy has a lot to do with understanding how the individual topics contrast with one another.

The researchers also discovered a second reason why interleaving works. Interleaved study builds a cadence in which learners have more time between repetitions of the same category. That is, they return to the first topic after starting the second topic. Then, they return to the first topic again after starting the third. This pattern keeps the individual returning to the first topic throughout the learning process. This spaced repetition contrasts with the blocked format in which the learner completes the first topic, then never returns.

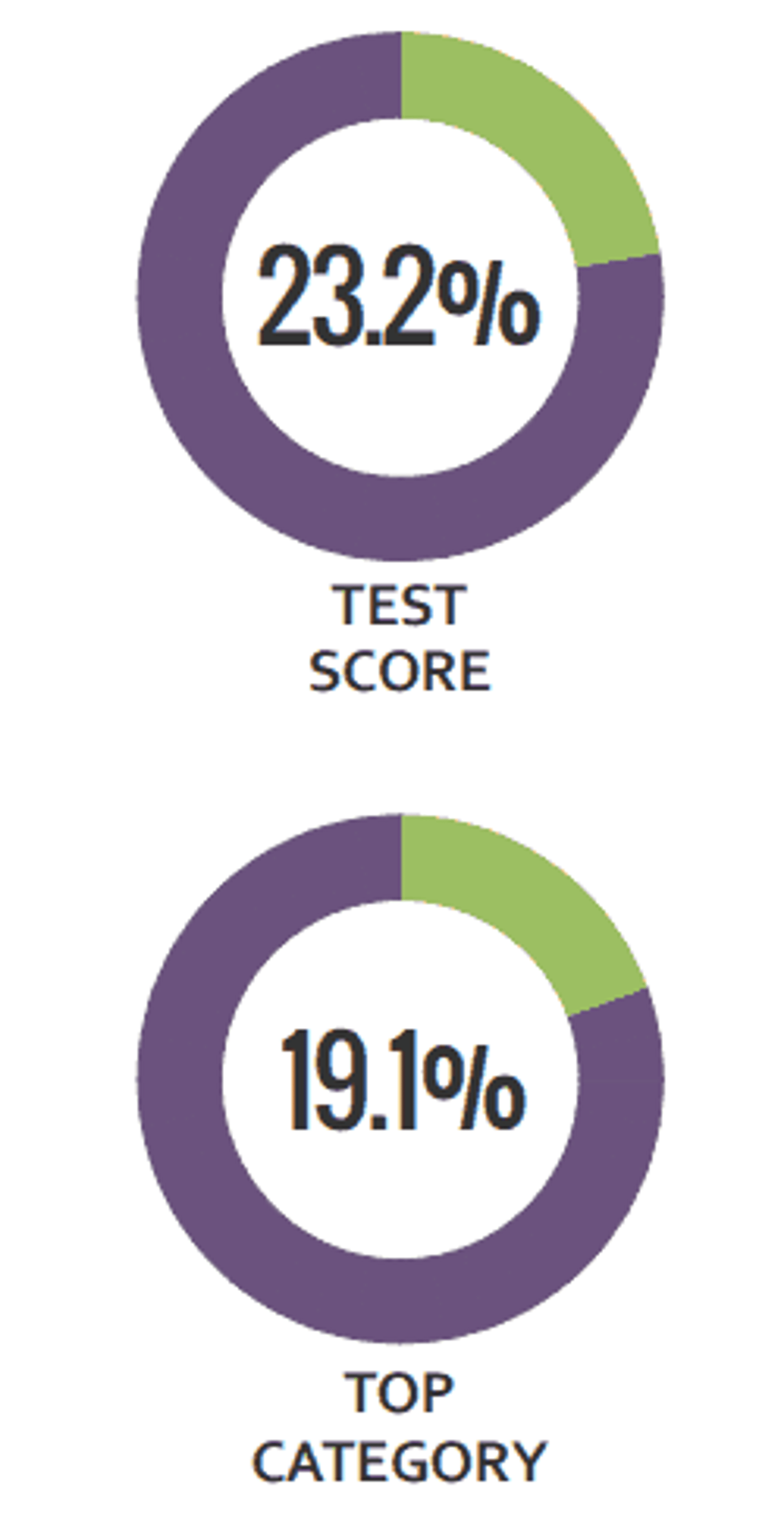

The benefits of interleaving have been proven several times. In a separate study published in the Educational Psychology Review, researchers found that “interleaving produced better scores on final tests of learning.” Like the research published in Frontiers in Psychology, the author explains that “when students encounter a set of concepts (or terms or principles) that are similar in some way, they often confuse one with another” and that “these kinds of errors occur more frequently when all exposures to one of the concepts are grouped together.”

How to Use Interleaving

Some may interpret the benefits of interleaving as an endorsement of multitasking. However, there is a difference between these two. Multitasking often encourages jumping from one item to another. Interleaving is different than multitasking because it is a structured approach that fosters learning through understanding the specific ways that similar but different material contrasts. Multitasking rarely involves a set of material that is interconnected. Instead, multitasking is often a random assortment of disconnected things. Moreover, research shows that multitasking creates inefficiencies because it carries what psychologists call “switch costs.” These costs are the lost productivity that comes from time needed to shift focus. As task complexity increases, so do these costs.

To avoid falling into a multitasking approach, learners should commit to interleaving in three ways:

- Commit to the Long Term: Interleaving is counterintuitive because it requires more time than the more traditional and more popular blocked approach. With blocked study, learners appear to grasp concepts faster. In fact, in one study, a group of participants engaging in blocked study averaged 89 percent correct in an assessment test compared to 60 percent correct among the interleaved group. However, one week later, upon taking another test, the interleaved group “boosted final test performance by a remarkable 215 percent” and vastly outperformed the blocked group. The bottom line: interleaving creates long-term gains.

- Draw Your Own Map: The benefits of interleaved study are clear. However, most instructional material has not caught up and is in a blocked configuration. Therefore, learners must take it upon themselves to map out an interleaved approach. Doing so means beginning with the first topic, then before long, moving to the next topic, even if there is unreviewed material remaining in the first topic. Keep moving to the next section even if the proceeding material has not been mastered. There will be opportunities to complete each section in full upon the second and third pass. Just because information is presented in a blocked style doesn’t mean it must be absorbed that way.

- Focus on What's Different: The power of interleaved study is that it underscores the difference between concepts that could otherwise be easily confused. Therefore, learners need to take the time to note these small but meaningful differences when engaging the instructional material. As the researchers in the book Make It Stick explain, understanding the commonalities among topics is far less advantageous than understanding the differences. Become a discriminating learner.

Effective Learning Means Reflecting

Many believe that the most effective way to develop new skills is to “learn by doing.” However, new research is reshaping this idea.

Researchers at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina theorized that reflection is an important but ignored part of learning. They discovered that learners who “are given time to articulate and codify their experience” learn more than those who don’t. In other words, learning accelerates with the dual approach of doing and reflecting. In fact, the researchers found that, at a certain point, more experience is less beneficial than spending as little as 15 minutes reflecting on training material.

This finding has important implications for sales professionals interested in getting more from training. To understand why reflection boosts knowledge retention, we must first look at the two traits critical for learning.

Critical Learning Traits

Reflection had a significant and measurable impact on learning because it “has an effect on self-efficacy and task understanding,” according to the researchers. Below, we look at these two factors and how they work.

- Self Efficacy: One’s confidence in their ability to exert continued effort and reach a goal. The researchers consider this trait an “emotional mechanism.” This sense of competence and capability is critical for maintaining motivation.

- Task Understanding: The knowledge needed to achieve an outcome. The researchers consider this second trait a “cognitive mechanism.” The more one understands a concept, the more resolute they become in putting it into practice.

Reflection is what the researchers call “deliberate learning.” In contrast, the researchers refer to practice as “experiential learning.” Their work doesn’t suggest that learners should choose one over the other. Instead, they urge learners to avoid the common trap of foregoing the act of reflection, which makes concepts stick.

Moreover, reflection cannot occur without first engaging in experiential learning. Deliberate and experiential learning resonate with our dual cognitive processes called system 1 and system 2 thinking.

Balancing System 1 and System 2 Thinking

System 1 thinking is like a quick-draw, shooting from the hip. System 2 thinking peers through the sight and takes careful aim. Both have their advantages. For example, system 1 thinking is helpful under time constraints. Reading text on a billboard requires system 1 thinking.

System 2 thinking is helpful when engaging complex concepts. Determining the price/quality ratio of two washing machines requires system 2 thinking.

These two examples come from psychologist Daniel Kahneman who won the Nobel Prize in Economics. In his bestselling book Thinking Fast and Slow, he explains that acquiring new skills requires both “an adequate opportunity to practice and rapid and unequivocal feedback.” The key is that learners need both the hands-on exposure (experiential learning) and feedback (deliberate learning).

Without reflection, we limit system 2 thinking, which is “associated with consequential decision making and explicit learning,” according to the Harvard researchers. We also need system 2 thinking because system 1 thinking is error prone. System 1 thinking lacks the careful reasoning required to learn new concepts.

In fact, system 1 thinking might be the reason so many people mistakenly limit themselves to deliberate learning. That is, we immediately jump to the idea that more experience is always better, even if it’s at the cost of reflection. The researchers explored this phenomenon, as well.

Where We Go Wrong When Learning

Researchers wanted to know if learners value experience over reflecting. They found that 82% of the participants chose to gain additional experience. Despite this overwhelming preference for experience, “reflection resulted in higher levels of performance.”

The choice to engage experience over reflection is understandable. Reflection can appear as wandering disengagement. However, the studies show that, when a learner takes the time to reflect, they outperform others. This outperformance is critical in a world of diminishing competitive advantages. Competing sales professionals have access to the same information and analytics. Those who are better prepared to leverage the full value of training will succeed. We live in a knowledge economy in which education and expertise are resources. Therefore, it’s more important than ever to be able to retain and leverage concepts learned in training. What’s reassuring about the study is that it offers a clear way to work smarter, not just harder.

Experience matters. However, experience without reflection is an incomplete approach to learning. Following these tips will help you and your team increase retention:

- Take at least 15 minutes to reflect on training.

- Connect with the material by writing about at least two key lessons learned

- Be as specific as possible, and return to the notes periodically to ensure that the concepts are clear. This approach crystalizes training and bolsters one’s confidence

Using the Pretesting Effect to Prime Learning

Traditionally, tests serve as a tool for measuring what we know. For most of us, this kind of assessment instills anxiety, but a study published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology may finally lay that anxiety to rest. Researchers from the University of California, Irvine have uncovered what they call the “pretesting effect.”

The researchers examined if failing a test can improve future learning. To do so, they evaluated the benefit of testing content before learning. This “pretesting” meant participants were likely to answer the questions incorrectly, given that they had not yet learned the material.

After taking this pretest, the learners were given the opportunity to read a selected passage, which covered the pertinent material. Then, they were tested again with both the pretest questions seen earlier and new questions. The results were striking. “Although participants largely failed on the initial test [answering 95% of the questions incorrectly], the effect of those failures was to increase retention of studied content.”

Here, we look at the results of the pretesting effect, reasons why it might work, and how learners can use it to their advantage.

Pretesting Primes the Learning Process

The success of the pretest group outpaced a second group that did not receive a pretest. Instead, they were given 10 minutes to study the passage before the first test. This group underperformed the pretest group on the final test. Findings like this reveal that testing has value no matter how many questions are answered incorrectly. That is, the act of taking the test serves to “prime the pump” for learning.

The results of the study have been remarkably consistent. The researchers conducted two additional tests. Here, researchers directed the non-pretest group to critical information by bolding or italicizing words and facts that would be tested later. However, the pretest group continued to outperform. In a third study, the researchers factored in a one-week delay. Again, the pretest group yielded the highest performance.

With strong results like these, some may ask if it’s even necessary to answer the pretest questions — why not just read them? An additional fifth study determined that “attempting to answer prequestion was significantly more effective than reading the same question and attempting to memorize it.” Pretesting always wins.

This is good news because the pretesting effect sheds new light on our understanding of testing. The study shows that pretesting drives learning rather than just measuring a baseline. Additionally, pretesting gives those taking the pretest reason to relax; poor test performance is less demoralizing with the knowledge that the score doesn’t matter.

Why Pretesting Works

Researchers are not certain why pretesting works; however, there are a few theories:

- The researchers in the Journal of Experimental Psychology suggest that attempts to retrieve information during the pretest lay the groundwork for building “retrieval routes between the question and the correct answer.” It’s also possible that the experience of pretesting encourages a “deep processing” of the question that would otherwise be lacking. The participants get a jump start on encoding answers.

- Benedict Carey, a New York Times reporter and author of How We Learn, suggests that incorrect answers prevent the “fluency illusion,” our misperception of what we think we know. This idea underscores a critical takeaway from the research: pretesting is more valuable for the learner than it is for the instructor.

However, calibration only works when the learner truly answers the question. It is not enough to read the question and decide that the answer is clear. It’s critical for the student to put pencil to paper and answer the question rather than just assume that they have a response.

Traditionally, learners are quick to dismiss pretests as a measurement that’s pertinent only to the teacher. The truth, however, is that the pretest serves the learner more than anyone. The pretest is not a “nice to have” — it’s a “need to have” that is, in a sense, loosening the soil in preparation for planting new information.

Though the “why” remains unclear, researchers are confident that pretesting works. Their findings show that pretesting and tests in general should be viewed as a learning tool rather than just a means to assess and measure.

The adage holds up — knowing the questions is more important than knowing the answers. Anyone can benefit from the pretesting effect by:

- Preparing for learning by taking a pretest of some kind. Try to find existing test materials on the subject and attempt to answer the questions. Remember, getting the answer correct is not important, but attempting an answer is

- Seeking out “back-of-the-book” quizzes and tests that are almost always present in learning materials

- Answering the question. Do not simply read the questions. Even if certain of the response, write it down to get the full benefit of calibration and the pretesting effect

Using Distributed Practice to Boost Learning

For more than 100 years, a finding called the “Ebbinghaus Curve” influenced theories about how we remember information. The curve — a downward sloping line — shows that retention of information fades over time. Some call it the “Forgetting Curve.” UCLA psychologists in the 1980s, however, discovered an interesting characteristic hiding within Ebbinghaus’s research.

They discovered that the original test subjects failed to remember the material because they were asked to recall a string of nonsense words like “sok” and “dus.” The participants couldn’t remember these words beyond a certain period because they had no meaning. Irrelevant information doesn’t stick because we have no location to store these meaningless letter combinations.

Later studies found that when asked to retain something meaningful like a poem, learners didn’t slide down the Ebbinghaus Curve — or, at least, not to the same extent. Since making this discovery, more researchers have learned that concepts must be relevant to stick. This relevance, or “salience,” engages with people on a personal level. As a result, they retain the information.

This finding underscores the complexities behind the way we learn. Our relationship with the material influences our ability to retain the information. For example, some theorize that struggling to retrieve information may, in fact, boost learning. The strategy built on this theory is distributed practice.

Here, we look at what distributed practice means, how it works, and how to use it to become a more efficient learner.

Distributed Practice

Distributed practice, sometimes called spaced practice, drives long-term retention by spreading out the learning process. This approach contrasts with massed learning in which a learner crams information, retains it for a short period, then loses it.

The problem with distributed practice is that the results are deceiving. Research published by the Association for Psychological Science shows that engaging in distributed practice can appear ineffective in the short term. In fact, when learners separated each of their six study sessions by 30 days, “forgetting was much greater across sessions.” Meanwhile, learners who put just one day between their study sessions performed better than the 30-day group. Moreover, those who put no days between the six study sessions performed best. These results would lead anyone to conclude that distributed practice is a flawed method. However, the researchers continued their study and learned that “the pattern reversed on the final test 30 days later.” The distributed practice group who had the greatest amount of time between sessions outperformed all other groups.

The benefits of distributed practice have led some researchers to delve deeper into the science. For example, work published in Psychological Science helps answer the question, “How much time should I put between practice?” The researchers examined how well learners retained information across 26 different conditions. The lag times ranged from no lag to as much as three-and-a-half months. They discovered that the optimal lag time depends on the required retention time. In other words, increasing the lag time also increases the retention time.

Learners who put 12 to 24 hours between their practice sessions can expect to retain the information for approximately one week. Those who put six to 12 months between practice sessions are likely to retain information for up to five years. This relationship is good news for professionals seeking to boost their|skill set because they can afford long lag times. Students preparing for a test have a limited period to use distributed practice, but professionals have their entire career.

The results from the research in Psychological Science are very specific. For most learners, it’s easiest to simply remember that the amount of time between practice sessions should be long enough for some forgetting to occur. Retrieving the information should be a challenge.

Unfortunately, learners rarely use distributed practice because traditional textbooks are not formatted in a way that encourages this method. However, today, more people are discovering the power of distributed practice as technology boosts adoption. Learning programs can provide periodic refreshers to learners via email.

Why Distributed Practice Works

There are several theories on why distributed practice works. As explained earlier, some researchers suggest that when we spread our learning sessions apart, we must work harder to retrieve memories of the previous session. This effort creates a more robust learning experience. Closer learning sessions mislead learners into thinking they know the material because recall is easier. However, the faster recall is likely due to recency, not proficiency.

Others suggest that distributed practice works due to consolidation, which is the process of converting short-term memories into long-term memories. Consolidating is like building a house. In the initial stages, the structure is weak, unstable, and easily altered. In time, the house strengthens. The frame becomes durable and able to withstand the test of time. Moreover, the initial structure is also disorganized, with building materials strewn about. They are disconnected and without association. Eventually, they coalesce, and the house becomes a well-defined structure. Frequent practice only uses short-term memory. Building a house requires more time than building the frame, however. A structure will endure, and a frame will fall apart.

Like a completed house, distributed practice is never truly complete. A home needs repairs, modifications, and reinforcements to the infrastructure. This constant “repair” work is what makes distributed practice effective. A brick house requires more effort, but it can weather a gust of wind better than a straw house.

Effective learning doesn’t occur in one, intense session. Committing material to long-term memory requires distributed practice in which the learner takes the initiative to put days, weeks, or months between each session.

You can leverage the benefits of distributed practice by:

- Using greater spacing for familiar material and less spacing for more difficult material

- Practicing spaced learning perpetually; the need to refresh never disappears

- Avoiding the false impression that cramming will work beyond the short term

Deeper Learning Starts By Asking "Why?"

Asking questions is among the most effective ways to expand knowledge. Perhaps that’s why it’s one of the oldest methods of learning dating back more than 2,000 years to the time of Socrates.

The Socratic method seeks to develop critical thinking skills and uproot faulty assumptions by engaging in questioning and debate. This style of learning is particularly useful for more complicated concepts that lack definitive characteristics. The Socratic method helps learners put an outline around complex concepts. However, finding the nuanced differences among similar pieces of material is challenging.

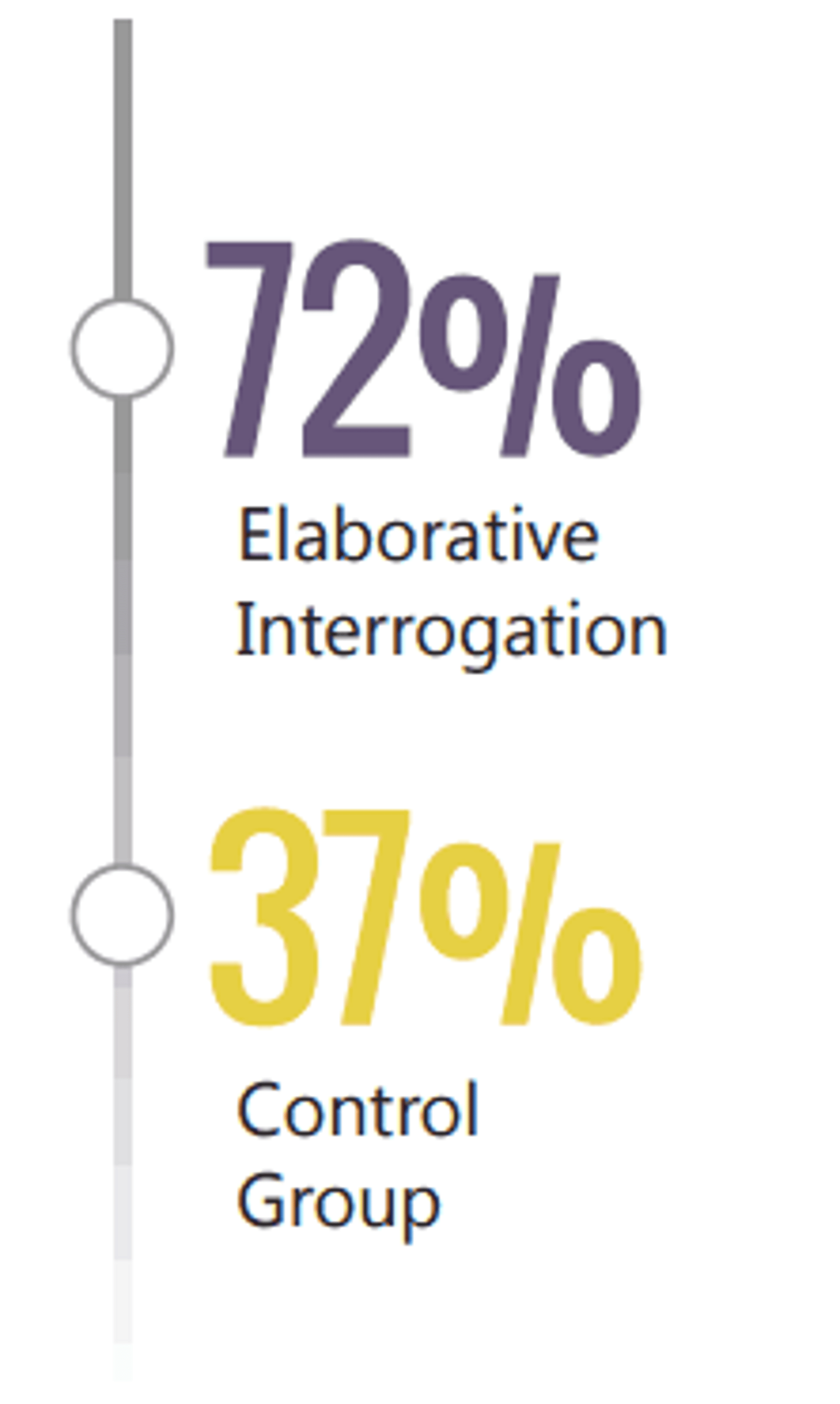

Fortunately, the researched-backed method of elaborative interrogation presents a helpful solution to this problem. Elaborative interrogation could be thought of as a modern day take on the Socratic method. This technique leverages the power of “Why?”

Here, we explore the idea of what elaborative interrogation is, reasons why it might work, and how to put it to practical use.

Elaborative Integration

Some have taken elaborative interrogation further and engaged in a similar method of learning called self-explanation. With this approach, learners are asked what the material means to them and their process for understanding the information. Both approaches work because they bring the learner deeper into the instructional process through questioning. The research shows that the quality of the participant’s answer to the “why” question doesn’t matter. The act of answering is what moves learning forward because developing answers helps the learner make sense of the material. Research also shows that elaborative interrogation is effective across learners of all abilities.

Elaborative interrogation is also a flexible approach to learning. Consider a study from Instructional Science, which showed that both open self-explanation prompts and assisting self-explanation prompts were effective in fostering procedural knowledge. What makes the approach so powerful is that it serves learners in the short term and in the long term. In the short term, learners immediately differentiate between alike material, thereby boosting their understanding of the concepts. In the long term, learners develop their critical thinking skills. In time, they learn to ask questions not only to serve their learning process, but also to challenge conventional wisdom that may be unfounded.

Why Elaborative Integration Works

Many researchers believe that elaborative interrogation works by integrating new information with existing prior knowledge. This process encourages the learner to make connections between new and old information. Perhaps this theory explains why additional research has shown that the benefits of elaborative interrogation increase when the learner’s existing base of knowledge is larger. Therefore, this method of learning is particularly useful to those seeking to build on their extensive foundational knowledge.

Others suggest that elaborative interrogation works because forming an answer allows the learner to make the information more idiosyncratic and personal to their understanding of the material. This feature of the method is important because relatability appeals to both the rational and emotional mind.

As with most effective learning techniques, the method may work simply because it makes the learner work harder than they’re accustomed to. This phenomenon is not dissimilar to the experience of someone who puts stress on their body by lifting weights or engaging in cardiovascular routines to build their physical strength and endurance. As researchers in the Journal of Educational Psychology offer, “It might be that the cognitive challenges presented by elaborative interrogation [in terms of reasoning with the information presented in the text] force the learner to construct a more complete situation model than he or she would otherwise construct.” Generally, elaborative interrogation increases the learner’s attention and effort.

How to Use Elaborative Integration

Effective elaborative interrogation questions encourage an analysis of both the similarities and differences between the related pieces of material. It’s often worthwhile to ask a variety of questions that offer a variety of ways to differentiate similarities in the learning material.

Even if the instructor doesn’t use elaborative interrogation, learners can take it upon themselves to leverage the benefits of the method through self-explanation. As discussed earlier, self-explanation is the act of explaining one’s reasoning for why an outcome occurred or for the steps taken to solve a problem. Learners should use both elaborative interrogation and self-explanation to help overcome misconceptions and faulty assumptions.

Finally, remember that deeper knowledge comes from deeper questions. Avoid the surface-level questions that lack specificity. Don’t confuse the technique with asking retrieval questions. Instead, focus on “how” and “why” questions.

Elaborative interrogation borrows from the time-tested effectiveness of the Socratic method. Learners can more effectively understand concepts by asking why. Research has proven time and again that answering specific questions about the material helps join new and old information and clarify nuances. Effectively leverage the concepts of elaborative integration in your professional training by:

- Attempting to answer specific “how” and “why” questions rather than simple fact-based questions

- If elaborative interrogation is not feasible, using self-explanation to talk through the reasoning used to arrive at a conclusion

Customized Sales Training Programs: Elevate Your Team's Performance

Our industry-leading approach to customization ensures your training program is relevant to your seller's world. Making lessons learned in training immediately effective in the field.

Learn MoreThe $70 Billion Investment

The challenge of living in a “knowledge economy” is no longer one of resource scarcity. Every professional has access to a vast reservoir of knowledge. Therefore, what differentiates one person from another is the ability to identify the pertinent information and efficiently absorb it into their routines. Unfortunately, much of what we’ve been taught about learning is incorrect or, at best, incomplete. Becoming competitive means stepping back and reevaluating how we learn. Consider that corporations in the US invest, on average, $70 billion on training with almost no spending on teaching how to learn. To become a better learner, commit to the following:

- Take at least 15 minutes to reflect on training. Connect with the material by writing about at least two key lessons learned, and be specific.

- Prepare for learning by taking a pretest of some kind. Try to find existing test materials on the subject, and attempt to answer the questions. Remember, getting the answer correct is not important, but attempting an answer is. Answer the questions. Do not simply read the questions.

- Approach material with an interleaved structure in which topics are mixed. Clearly define the contrasts between similar concepts in order to strengthen learning long after training is complete.

- Seek opportunities for group learning in which the process of skill development is shared.

- Use verbal and visual cues together — doing so might require drafting quick sketches of abstract concepts.

- Put time between learning and study sessions, and use more spacing for familiar material and less spacing for more difficult material

- Attempt to answer specific “how” and “why” questions about the learned concepts rather than simple fact-based questions.

Boost learning with Richardson Sales Performance Accelerate™, a platform providing various online sales training programs that sits at the heart of a blended learning solution. It is built to engage and inspire sellers, provide real-time visibility into performance for sales managers, and drive long-term results.

Brochure: Accelerate Sales Performance Platform

Learn more about Richardson Accelerate, the sales performance platform at the heart of our blended learning training solution.

DownloadGet industry insights and stay up to date, subscribe to our newsletter.

Joining our community gives you access to weekly thought leadership to help guide your planning for a training initiative, inform your sales strategy, and most importantly, improve your team's performance.